Pieceworks and parts

Edwina Corlette Gallery, Brisbane

18 June – 8 July 2025

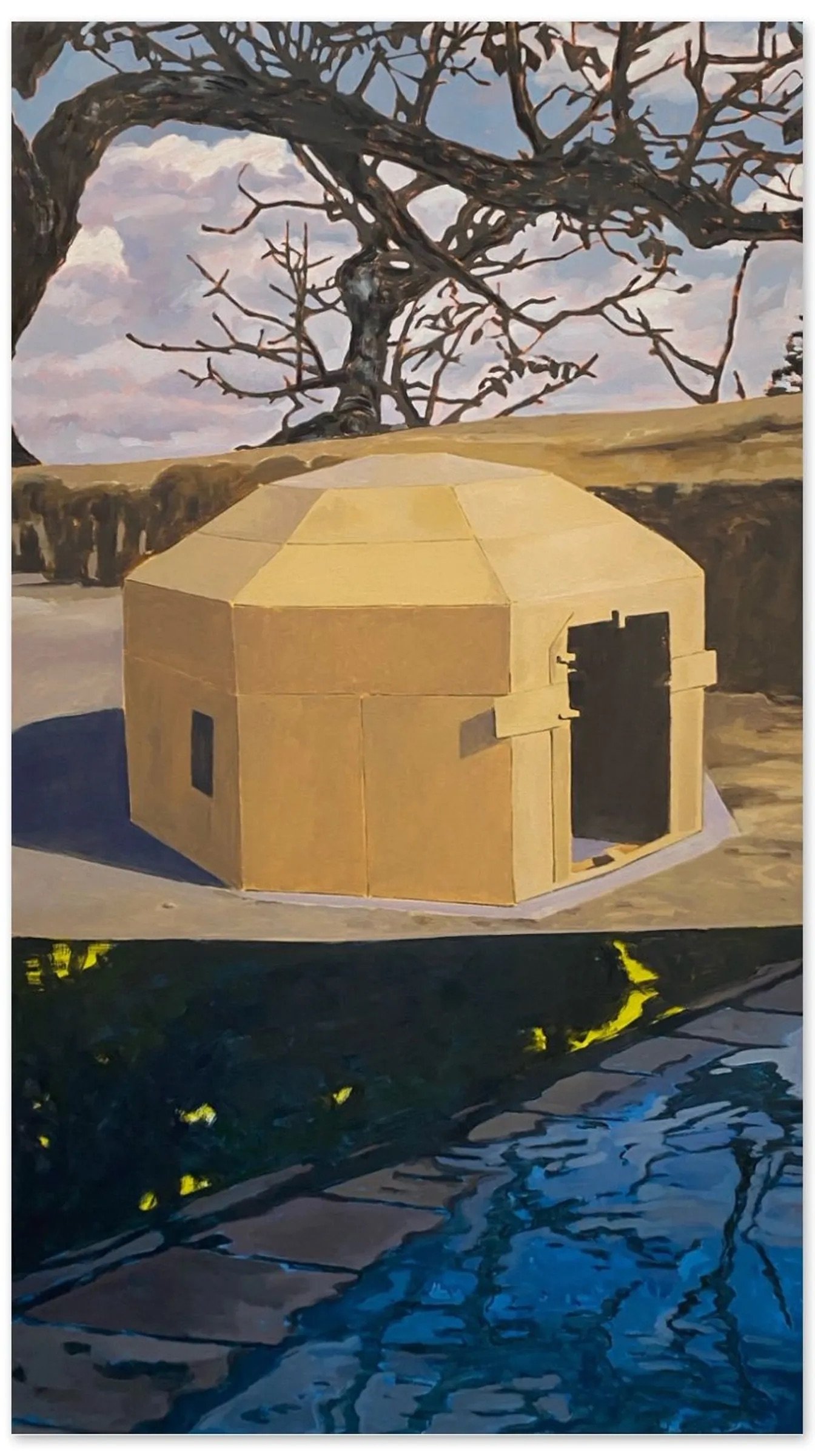

Piecework and parts, 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas, 153 x 137 cm

The water above 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas, 102 x 107 cm

Orpheus sings 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas, 102 x 102 cm

Eurydice 2025, acrylic and oil on canvas, 153 x 86 cm

Living in the ruins 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

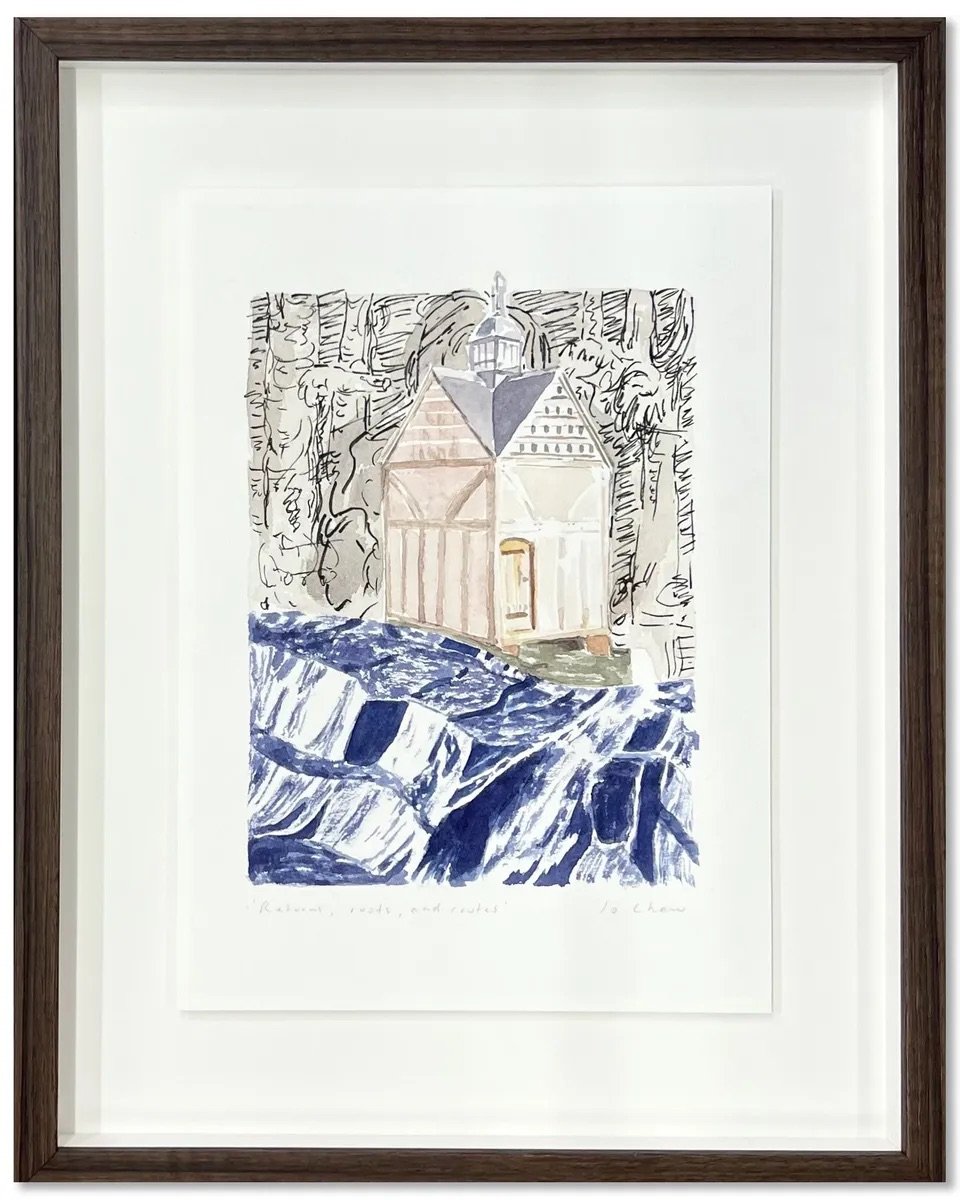

Returns, roots, and routes 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

Piecework and parts 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

Generative joy 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

Eurydice 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

Holding still 2025, watercolour on paper, 41 x 32 cm

Installation images courtesy of Louis Lim

Pieceworks and Parts - catalogue essay

Written by Andrew Harper, June 2025

Hades, moved to tears by the song of Orpheus, agreed to allow Eurydice to return with her lover.

Hades gave instruction: Orpheus was not to look back at Eurydice, who was to walk behind him. Orpheus was unable to hear her tread, and fearing a deceit, disobeyed.

Eurydice, who was dead, did not make noise when she moved.

Eurydice, who was dead, would not return to flesh until the sun warmed her alive again.

Hades had never before allowed the dead to return.

A song made the dour and strict ruler of the underworld bend his laws. Think on it: a song so filled with longing it could move the gods.

And yet Orpheus looked back.

It is as if he did not trust himself.

Hades, having made a ruling like no other, would not change his mind.

Eurydice, who was dead, would not see the sun again.

Nor would Orpheus join her in death.

Wandering, singing in madness at his own foolishness and the horror of his loss, Orpheus was torn asunder by the Maenads of Dionysus, who had grown weary of his endless keening. Orpheus, whose song had overpowered that of the Sirens, was left only as a head, still singing, undying, until a temple was built to house it and he became an oracle.

Perhaps, on some far Aegean Island, he sings still.

Humans survive.

From the coldest ice to the driest deserts upon the wide earth, there are people. People – humans – are good at thinking laterally and working out how to live where ever they might be. Humans use tools and they make tools. Humans use things in ways unexpected, making new from old. They can do astonishing things when they work together, sharing ideas, telling stories and whispering songs to send their children safe to sleep.

No matter how hard the world becomes, humans will always try, will find ways. People lose everything and do not give up. They survive.

Jo Chew’s art sees this and works with it. Jo sees how people make shelter, and how they want shelter, and what they do, not matter where they are. Her paintings are complex reflections of human needs and drive, derived from a long sifting of the varying hints and echoes that grew from her realisations about people and how they make their homes.

She began with seeing homelessness, and showing that; not as a disengaged observer, but as someone who was very close to that edge. After all, many of us are, and more of us are all the time. Things change in life, and the questions of security move about, taking on new forms.

How are we to survive now?

Jo has no answer to this, but she does not shy away from the question.

Over time, her work has moved from a direct engagement with the reality of homelessness to examining the world that homelessness occurs in. She looks for the images and fragments that can be pieced together to create a new vision.

Jo looks at images. Some she searches for, others come to her; since the growth of mass printing culture, and then the internet; there are images everywhere, adrift. She follows that tide, glimpsing ideas.

Jo gathers them, placing them together to create new context, finding more complex meaning and seeking new visions. This is an important aspect of her process, borne and informed by that human ability to find the new and use what’s there to create. She finds a picture of an earthquake shelter, a temporary dwelling that is always ready, positions it above a darkened reflective passage of water, and it becomes Eurydice, that lost love of Orpheus, left in the underworld. It is new myth made of old.

But it is not just finding images.

Jo paints, and the act of painting is central: it completes the process.

The paintings are not two found images placed together: they are a finished work, made entire, with no edges or overlap, perfectly merged to realise entirely the vision she has made.

Her work is always about painting as much as it is about seeing and thinking: how things are painted is part of the work, and if something is not finished, it was because it could not be: the house that seems unfinished in Piecework and Parts is a home out of reach; contrast this with the fully realised tent of Orpheus sings. The painted image is not a representation; it is an act of creation in motion. Each work, even the ones incomplete, are finished. Lifted from fragments, they become complete, even when they are unfinished: everything says something. There is so much in each work.

Jo Chew paints the idea of shelter, the hope for safety and the possibility of human achievements: she understands what can be done when people come together; how they might build, how they will negotiate challenges, both interior and exterior. Many of the dwellings are temporary, moveable and small, yet they are still shelters: permanent in their impermanence, they represent the ability to react and respond: carry the tent with you, just as you carry the things you hold dear in your heart and mind. It is enough to keep you safe, safe for now, and when you work with others, your tents are a village, and you are stronger still.

Home can be built of fragments we find and carry, and they will become complete, they will be enough.

Jo Chew’s paintings are infused with hope, with memories of shelter and the necessity of making what you can, with what you have. They reach backward and forward in our lives; they come from play and are pitched in the real. They straddle a line of warning and resilience and understand that we make our shelters in our minds just as much as we make them with our hands.

The story of Orpheus has no one author, no one ending, and is open, yet it sings to us across time of love lost.

No one made this story, and it is still being made: whenever an artist is moved by it, whenever they find something in it, its fragments mean something new.